The Hills Are Alive

What do we mean when we talk about transformation? A Dispatch from the Future Earth Autumn School.

This month’s post is a dispatch from the Future Earth Autumn School, which the RCSC attended. 50 academics and sustainability practitioners from across Europe gathered in the Alps at the cusp of a seasonal transformation, under the theme “transformative research for a just world and habitable planet”. With record high temperatures and record low levels of snow, the school was also haunted by a dark wave of change around us; a heavily critiqued UNFCCC COP where the global south was once again left without sufficient commitment to climate finance, and the rise of the extreme right in Europe and the Americas and the ensuing doubling-down of anti-migrant rhetoric and policy. It was duly noted by the organisers that the center we gathered in was established by and named after Paul Langevin, someone equally well known for his contributions to physics as to the anti-fascist movement in the 1930s and 40s.

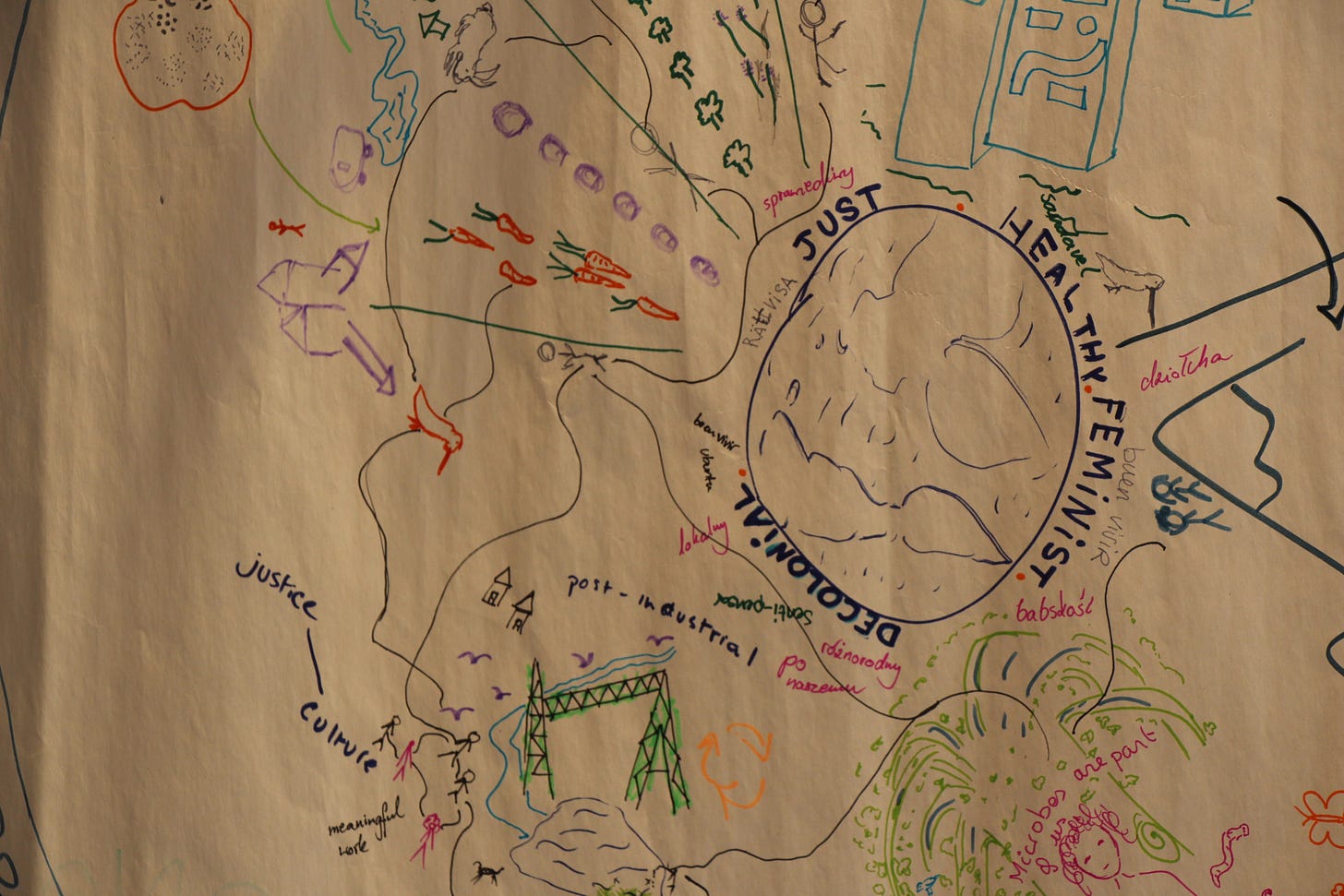

The Autumn School involved practical workshops and deep thinking on how to co-create transformation, as well as how to plan for the types of futures we want to see - back-casting from visions to distinct societal interventions. We talked about changes from both the inside-out and bottom-up, asking what is needed to materially change how we relate to the natural world based on an ethic of planetary care and justice. With guidance from practitioners and fellow action-research participants, we workshopped practical ways to engage with and transform local situations facing wicked environmental and social justice challenges; to take one case example, post-fossil extraction zones in Europe which often face interrelated social issues, environmental toxicity and degradation and green-corporate capture. Visions here included transformative legislative and democratic means, such as granting mountains and rivers personhood or constructing citizen’s assemblies. Together with local actors, we also delved into the place-based challenge of transitioning towards a ‘post-ski’ future in the Alps.

A recurring question, however, concerned the nature of transformation. What does it mean exactly? A complete change from one form, system or process to another? A change around the edges? Reform? Revolution? The rhetoric of transformation, as with sustainability, brings with it the risk of meaning everything and nothing. ‘Green’ transformation has become another low-hanging target for greenwashing. Big Oil has adopted the rhetoric of transformation to ‘net-zero’, a scheme critiqued by many as a dangerous trap employing methodologically and ethically questionable means (i.e. geoengineering and carbon-capture and sequestration) in order to allow continued expansion of fossil-fuel extraction (see this review from climate scientists).

The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) defines transformative change as “a fundamental, system-wide reorganisation across technological, economic and social factors, including paradigms, goals and values”. Shifting the focus from “systems” to “society” has been proposed as a more actionable focus by Visseren-Hamakers and Kok (2022) – challenging us to broaden our lens in the quest for effective levers of change.

A new article from Querine et al. – “Varieties of anticapitalism: A systematic study of transformation strategies in alternative economic discourses” pins the necessity of transformation on the underlying structures of capitalism - the indirect driver of (un)sustainability - critically dissecting and exploring alternative economic pathways. Transformation in the radical sense – as in from the root – is what is needed to correct humanity’s course and restore our relationship with the natural world. As the saying goes, “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism”. It is therefore precisely these types of explorations that are key in forming post-capitalism, post-extraction and post-growth imaginaries.

We can also take our cue from nature, and its indigenous stewards, when we ask what transformation means.

We can think of seasons, metamorphosis, compost, all changes from one form to another. This month, researchers reported that climate dictates whether a species of tiger salamander will alter its phenotype to adapt to either a terrestrial or aquatic environment, adding to the growing number of ways climate change impacts biodiversity. Talk about climate-induced transformation.

The mountains surrounding us at the Autumn School offered a rich contemplation on transformation. Mountains with their sleepy consciousness – not unconscious, but awake on a scale that is so slow it is almost incomprehensible. Looking at the creases and spikes and folds we can imagine the seismic ripples upon the touch of continental plates. They are sentries watching over us, a reminder of geological time.

In a way, mountains are un-transformable. We can drill through them, slide down them, decorate them with electrical cables and gondolas like a giant altar. But we can’t wipe them out. We can’t mutilate them in quite the same way we have the low-lands. They stand as a reminder of the force of nature, forcing us to reckon with our absolute smallness, and with our mortality, in a way that has been castrated in so many urban areas.

Yet there has also been mountain transformation in the span of one lifetime. We see snow disappear and numerous species creep higher and higher, we see glaciers melt before our eyes, we see winters – that precious time of regeneration, reset and transformation – shorten and soften. Scales of transformation collide.

In Zen-master and Indigenous Hawaiian leader Norma Wong’s new book “When No Thing Works: A Zen and Indigenous Perspective on Resilience, Shared Purpose and Leadership in the Timeplace of Collapse”, we are similarly challenged to rethink our timescales of transformation. When we look back – can we look way-back, back beyond any ancestors we know of or knew? We don’t know their names, or maybe even where they lived – only that they were on a land that they cared for. And when we contemplate futures – can we push our conception of future generations? Can they be so distant that we don’t know their names or relationship to us – only that we are caring for and holding the earth for them? Living today with the possibility and conviction that they may live then.

As we research and teach and choose our pathways into the future, may we be challenged to think not only of what a transformed world looks like, but what timescales of transformation we are imagining and what will allow us to get there. Our last great transformation as a society was into the Anthropocene, coming in blazing with technology, progress and man-over-nature arrogance. Yet to paraphrase two intellectual giants, a problem can never be solved in the same plane of conception within which it was created, or, the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. So let us hold our compass to the direction of nature.