Sustainability Dispatch: Is the Paris Agreement dead?

A new monthly blog series for the Sustainability Dispatch. This month, a reflection on global climate governance.

Dear Readers,

With this post we are excited to launch a new regular blog series on Sustainability Dispatch. Reflections on a timely theme each month will link to a curated selection of news, articles and multimedia content, hopefully of interest to our readers. We intend for this to be full of resources and conversation starters to equip you in your work on transitions. This month, we reflect on the state (and practice) of global climate negotiations in light of the upcoming Conference of the Parties (COP) to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

As we look towards the end of 2024 and COP29 in Azerbaijan in just a few weeks’ time, we are at the same time reflecting back on nearly 10 years since the Paris Agreement. Ten years. I’m sure many of us can remember, if not where we were, but the feeling we had when we learned that climate leaders had signed the celebrated agreement. A sigh of relief, that we had taken a step – if perhaps too small a step – but a step, collectively, to dam the literal and metaphorical tide of climate change. It wasn’t long before critics described the agreement as a series of broken promises, destined to failure given the lack of legally or otherwise binding agreements.

Sitting up and looking around at the end of 2024 might feel like waking up with a terrible hangover and fuzzy idea of how we got here – waking up to 10 years of climbing temperatures, catastrophic weather events, biodiversity loss, stalled or faltering attempts to legislate keeping fossil fuels in the ground.

Realizing we have not only failed to limit warming to 1.5oC above pre-industrial levels - we reached this milestone in 2023, and are on-track to do so again in 2024 – but have also not followed through on other critical (and non-legally binding) commitments. For example, insufficient transfer funds for adaptation and so-called ‘green development’ in countries of the Global South, leaving areas already suffering from catastrophic climate events unable to implement the social and material infrastructure necessary to cope with what they are not historically responsible for. According to the latest report from Climate Action Tracker, aggregate emissions and policy changes since 2015 show little change.

The Paris agreement has been lauded as our best shot so-far at curbing climate change. The 1.5 degree limit imposed is the cumulative result of decades of climate science and policy advice from thousands of the world’s pre-eminent climate scientists. The climate models they generated are worryingly uncertain when it comes to feedback loops and potential tipping points, yet at the same time abundantly clear: surpassing 1.5 risks catastrophic climate change.

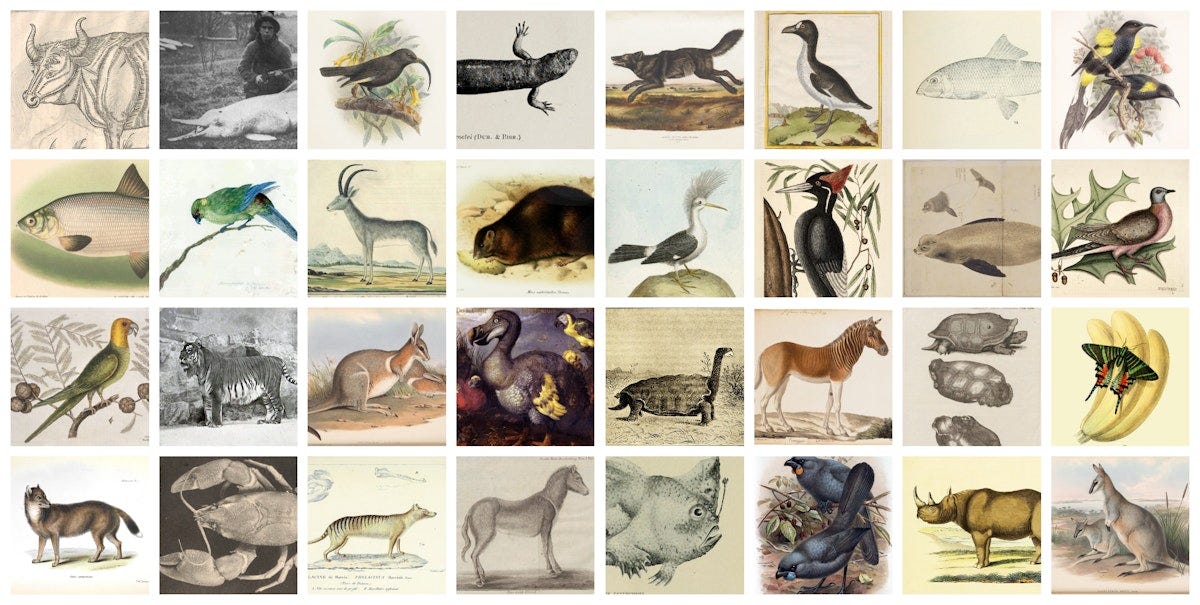

In the words of UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres: “In concrete terms, this level of global heating means major cities under water, unprecedented heatwaves, terrifying storms, widespread water shortages, and the extinction of one million species of plants and animals.”

There is now an active lobby, the loudest voice in the choir being the oil and gas industry, to push the limit of acceptable warming to 2.5 oC, knowing full well that this risks catastrophe of an unknown scale. A comprehensive analysis published this month in Nature maps pathways for overshoot of 1.5 oC, and find ‘considerable uncertainties’ in whether we could find our way back to 1.5, and worrying overconfidences in models which attempt to predict how the earth responds to further temperature increases. Indeed, researchers reported this month that they observed an alarming collapse of terrestrial Carbon sinks in 2023, which was not accounted for in climate modeling. These findings reaffirm that in order to ensure planetary well-being, we must stick to 1.5. But, we aren’t. So … now what?

Conference for People and Planet or Conference of the Status Quo

Thousands of delegates fly from all over the world, year after year, to engage in an elaborately staged performance of diplomacy. The COP is not only a venue for political negotiations, but a corporate fair where thousands of ‘green’ and oil and gas industry professionals vie for a chunk of change in helping to carry out countries’ energy transitions.

Naturally, this is an arena soaked in the most insidious forms of greenwashing such as net-zero strategies and peddling of ‘low carbon’ liquid natural gas (LNG) (for an excellent dissection of this, check out this episode of Planet Critical). A recent study finds that the carbon footprint of LNG equals or exceeds that of coal, exposing a decade of deception and manipulation by the oil and gas lobby to paint it as a climate-friendly alternative.

Beyond the failed climate targets and profusion of greenwashing, COPs of recent years have been ripe for critique of their blatant and perpetual blind spots when it comes to human rights abuses.

COP29, “In Solidarity for a Green World”, sets their sights on “delivering deep, rapid and sustained emissions reductions now” in order to avoid overshooting 1.5. Azerbaijan has been accused of using the COP as a smokescreen for its ongoing human rights abuses (see also this report from Human Rights Watch), as was COP28 in Dubai in 2023. COP29’s presidency affirms their intention to deliver these transformations while (in their words) ‘leaving no one behind’. One would be justified in asking whether this includes the over 100,000 ethnically cleansed Armenians from the Nagorno-Karabakh region following its occupation by Azerbaijan in September 2023. Successive military offenses have resulted in thousands of deaths, including civilians, since the early 1990’s.

Another signatory to the UNFCCC COP is Israel, charged at the International Court of Justice with the illegal occupation of the Palestinian territories and plausible genocide. Twenty ‘climate tech’ companies from Israel are set to be present at COP29, which, alongside other areas of the Israeli high-tech sector, are likely to showcase green strategies which have for decades acted as one of the major fronts in the normalization of Israel’s process of settler-colonialism, illegal occupation, apartheid, and now genocide.1 A prime example is the water and energy apartheid playing out in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT), where Palestinians are denied access to both the electricity grid and groundwater. Mekorot, a major ‘climate tech’ corporation in the field of desalinization, also controls the vast majority of water resources in the OPT, diverting them to illegal settlements. Bringing this to the doorstep at COP29, in 2023 Azerbaijani news announced that the country has signed a deal with Mekorot to desalinate water in the Caspian Sea. This so-called ‘eco-normalization’ reinforces Israeli greenwashing while undermining a just transition in Palestine, directly linked to their struggle for self-determination.

To quote Amnesty International’s secretary-general: “It’s patently clear that no state can have any credibility in addressing the climate crisis while continuing to tighten its chokehold on civil society".

Heading into this year’s COP, we must remain critical. Do we hold the COP accountable in their perpetuation of white and green-washing of the grave crimes against humanity, or must we necessarily shelve these concerns in the name of (possibly) reaching a united agreement to halt climate change? Leave no one behind we should not, but leave behind practices of extractivism and dispossession, especially those predicated on (neo) settler-colonialism we must.

Real awareness

If any of us had the magic formula to bring binding global accords to tackle the climate crisis into being, we wouldn’t be where we are today. It is high time to be very real, and very transparent about why it is that we’ve known about climate change for decades, yet have utterly failed to halt fossil fuel extraction and emissions: the multi-billion dollar oil and gas industry and their politically embedded lobby, and the interlinked mass wealth accumulation based on ongoing (neo)colonial extraction from the Global South. In the framework of a just transition, this means that to decolonize we must also decarbonize, and to decarbonize we must extract ourselves from the pervasive economic systems governing our world which run on the law of wealth accumulation, not well-being of people or planet.

What is critical here is a base literacy on the systemic causes of the crisis we find ourselves in, and a focus on possible routes towards mass economic reform (and/or revolution). How could a binding global accord work? What radical economic and governance reform is needed? How do we overcome (and abolish) the lock-ins and corporate capture preventing nations and regions who wish to transition from extractive industries but are as-yet unable? While our collective inaction may have killed Paris, we have no choice but to continue to demand a systems change grounded in actual material practice such as divestment and an end to corporate subsidies.

We must also continue to ask: how can we do this better? How do I, as an individual best confront the task of meaningful systems change, without reproducing harm? Literacy and putting our body at the blockade are one thing; being present in our fear, anger, grief and confusion are another.

We can take tremendous inspiration from the practices of one of the champions without whom the Paris Agreement would not have come to be, Christiana Figueres. In her own account of how a practice of mindfulness, deep listening and compassion was critical in achieving this agreement, Christiana has reflected that “if you do not control the complex landscape of a challenge (and you rarely do), the most powerful thing you can do is to change how you behave in that landscape, using yourself as a catalyst for overall change … By delving into our own vulnerability we humanize ourselves, and that is where we connect to each other and all of a sudden can discover where the power really lies – the power to change and the capacity to improve and work together are really there.”2

The Sustainability Dispatch will continue to explore such topics at the intersection of higher education, governance, justice, and how we operate within complex systems; and how we might dare to change these structures, starting with our own ways of relating to ourselves and the world around us. Our call to action is (and will continue to be) to dare to imagine another world that might come to be within our lifetime; another world where it is luxurious and aspirational to live an ultra-low consumptive, ultra-low impact lifestyle; where we have made tangible strides towards restorative justice; another world wherein, to paraphrase Freire, it is easier to love.

Footnotes

1 Shqair, 2022. Arab-Israeli Eco-Noramlization: Greenwashing Settler Colonialism in Palestine and the Jawlan. Dismantling Green Colonialism, Pluto Press.

2 Thich Nhat Hanh, 2021. Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet, Penguin Random House.